Six free plays to help theatre-goers on lockdown, along with lots of interesting content and even the show’s programmes, have been made available by Shakespeare’s Globe. My first choice, the one I most regretted not seeing when I had the chance, was Michelle Terry’s performance as The Dane. Marking Terry’s appointment as the venue’s artistic director in 2018, while a female Hamlet is nothing new, it was a bold risk. It’s pleasing to say the confidence paid off – Terry is fantastic and the production very good.

Directed by Federay Holmes and Elle While, aside from having a woman in the title role (which surely shouldn’t shock… but still) this is a sensible, even traditional, show. There are even, mostly, period costumes in Ellan Parry’s design – all a part of rendering the play accessible and the delivery natural. As a part of these admirable qualities, this is also a snappy show, just over two-and-half hours, with sensitive cuts and an unerring eye on keeping the action moving.

The production is a model of clear-thinking. Benefitting most is James Garnon’s Claudius, whose delivery is remarkably fresh. A poor schemer (after all, most of his plots fail), he often seems confused and struggling with the situation – an interpretation that adds interest and tension. Garnon’s is an understated performance, a quality shared by Helen Schlesinger’s Gertrude – at first frosty, “when sorrows come”, she reacts magnificently.

It might be better if the admirable restraint was universal. Shubham Saraf’s Ophelia and Bettrys Jones’ Laertes both come across as hysterical in contrast; their roles are used as a foil to the royal family a little clumsily. And I suspect it will surprise no one that Pearce Quigley’s Rosencrantz is played for laughs: in this instance his comic talents are something of a shame. The accompanying Guildenstern (Nadia Nadarajah) uses sign language, which proves fascinating, and Quigley comes across as a distraction.

These are quibbles in what is a very fine production. Holmes, While and Terry carry clarity into the production’s argument. Of Hamlet’s actions and emotions, they would claim, “it is not madness” – a position adhered to with consistency and made convincing. Terry delivers the “wild and whirling words” with credible mania. And she can be scary – not just when she looks like a demented clown. But what happens if you don’t think Hamlet is mad? Taking him as “sweet and commendable”, Terry invests incredible emotion into his plight. The soliloquies are always intense, but Terry makes them more emotional than ever. Like the “sweet Prince”, I often had a tear in my eye, making this a Hamlet to remember.

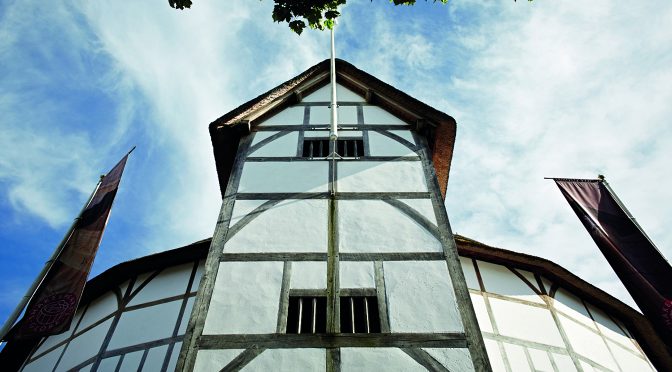

Photo by John Wildgoose

Available until 19 April 2020 on globeplayer.tv

To support visit www.shakespearesglobe.com