Laurence Boswell’s adaptation of a Dostoyevsky short story, into a monologue for Greg Hicks, is undoubtedly high quality. It’s always worth a trip to see Hicks, who is one of the most commanding performers around. The delivery is magnetic and matched by Boswell’s confident direction. But the overt profundity of the piece might be a turn-off, unless you’re a big fan of theatre with a message.

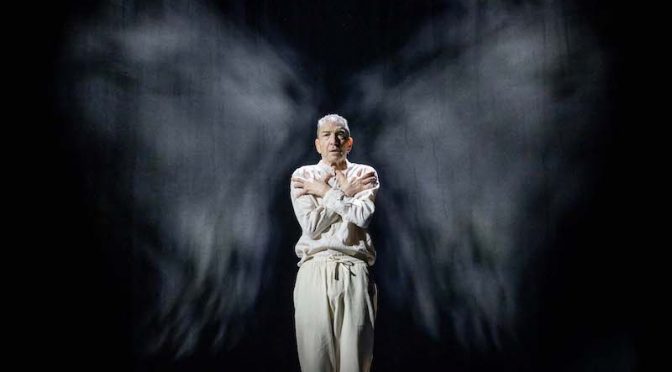

The dream in question occurs on the night our nameless narrator is about to kill himself. Hicks and Boswell set the scene for depression with relative restraint. We don’t have to like or trust our storyteller. Updating the action and location isn’t a bad idea either; we’re in 21st-century London and all the anxiety on stage is recognizable. It’s intriguing and all aided by Loren Elstein’s excellent design, which uses shadows and projections.

It’s when the dream starts that problems occur. While the production continues strong, Ben Ormerod and Gary Sefton’s work on lighting and sound is great, the allegory of a paradise visited is pretty standard stuff. The island, described as Eden, peopled by “children of the sun”, is easy to locate in a 19th-century imagination. Subsequent concerns about corruption and colonialism are also dated and too swiftly addressed.

That’s not to say ideas about loving one another, or listening to each other, aren’t important… just that they aren’t dramatic in themselves. There are some neat nods to theatricality towards the end, including a great reveal of the props that have been used, and even a joke (just the one): what we’re watching is usually a “guerrilla gig” and it’s nice to be indoors! But it isn’t a surprise that a vision is proselytized or a message of hope ignored. While Hicks is strong to the end, the play is more of a sermon than a show.

Until 20 April 2024

Photo by Mark Senior