Visiting the London Coliseum this summer, New York’s Lincoln Centre’s revival of Lerner and Loewe’s masterpiece matches the musical’s classic stature. Like the piece, the production oozes quality from start to finish. The show is as consistently close to faultless as you could wish.

It’s the story of flower girl Eliza Doolittle and her Pygmalion transformation by Professor Higgins and Colonel Pickering. But, of course, you knew that. The way in which the lower-class Eliza is treated by the toffs is handled with as much sensitivity as it can be. Director Bartlett Sher’s adoption of a thoughtful pace allows nuance to come through.

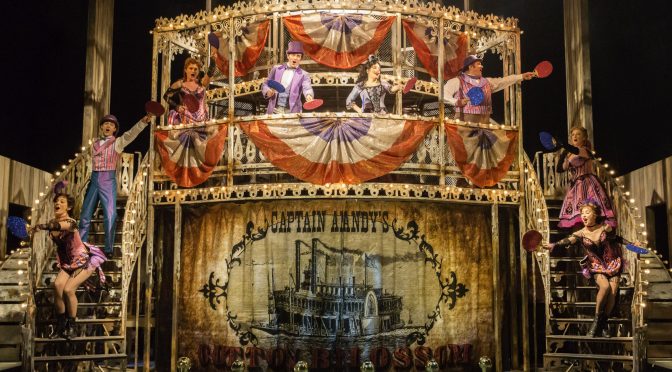

The slow(ish) treatment – there is little action here – might be expected to make the almost three-hour show drag a little. But entertainment is guaranteed by the hit score and the consistently clever lyrics. The cut-out-style sets (Michael Yeargan), including Higgin’s revolving home, are appealing, while the costumes (Catherine Zuber) are full of inventive touches.

The production’s biggest strength comes with the strong cast. There is excellent support from Shariff Afifi as Freddie, who sounds wonderful. And strong work from Maureen Beattie’s housekeeping Mrs Pearce. Just don’t get too excited for the too brief appearance of Higgins’ mother (Vanessa Redgrave). Malcolm Sinclair takes the part of Colonel Pickering in his stride – an effortless performance that is a joy to watch. Above all, the leads are a delight. Amara Okereke makes an excellent Eliza, balancing the character’s fearful and feisty qualities; her voice is one of the sweetest I’ve heard but can also be full of temper. Okereke manages to make the number Show Me her own. Travelling with the show from the States, Harry Hadden-Paton is a suitably imperious professor with impeccable comic skills.

Sher is respectful of the show’s heritage all the way to the end. It’s a great moment but, overall, the production is a traditional affair. For critics, the show suffers a little in comparison to another US import, a radical reimagining Oklahoma! at the Young Vic. But few will question these performances or the forceful vision behind the show. Making sure a musical like My Fair Lady gets its fair due is a fantastic achievement.

Until 27 August 2022

Photos by Marc Brenner