Rory Mullarkey is a playwright who explores allegory and fable. It gives his voice standout and makes him easily described as experimental. Self-conscious in telling tales and quick to point out quirks, his skill is clear, and this story of a “completely and utterly archetypal town”, subjected to a series of incredible tragedies, gets some big laughs. It’s the treatment, a mix of the ludicrous and the deadpan, that is the focus and used to examine our compassion. Arguably, this investigation of delivery – the way the story is told – while of keen interest to theatre practitioners is clearly of less appeal to a general audience.

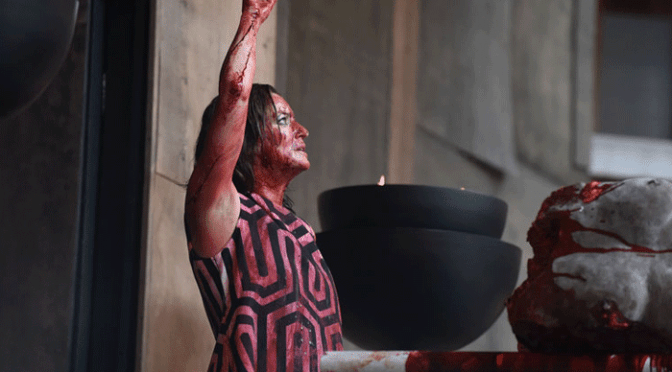

While stripping the scenario back seems to make a distinctly academic point – I am open to suggestions, but the text is so reductive it rules out other options – it is an achievement to stage something so stark. Characterisation and plot are reduced to parody. Mullarkey’s imagination is fecund and his play full of exaggeration, as the mostly nameless characters meet and die in ever more inventive fashion. Bringing the events of an apocalypse-in-a-day to the stage takes real guts.

This is a mixed job from director Sam Pritchard. His tactic seems to be to maximalise. Along with Chloe Lamford’s set and plentiful props, most of which fall from the sky, we have quirky movement direction from Sasha Milavic Davies, and lots of noise and lots of lights. But added together, it all highlights the script’s flaws and makes the show too slow, with too many speeches padded out. Some ideas are good (I liked the brass band and the tanks), but others, like an extended battle between the Reds and the Blues, repeated ad nauseum, are truly terrible.

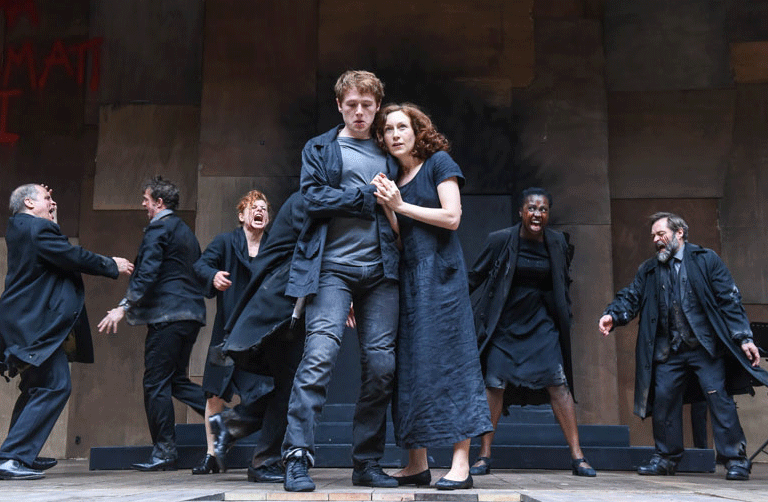

Pritchard does well with his cast: a committed ensemble who seem to be having fun. Sophia Di Martino and Abraham Popoola take the leads as survivors of events. After overcoming each disaster, they tell each other, “I’m all right”, and they manage to make this tiresome repetition almost effective. And there’s great work from Helena Lymbery as the Prime Minister and Sandy Grierson as the Red Warlord. But all the cast impress. Time and again, they save scenes with charm and bring out Mullarkey’s humour. There’s a lot of bravery here, not least with the play’s hostage-to-fortune title, but no amount of effort or energy manages to make it all worth bothering with.

Until 11 August 2018

Photo by Helen Murray