Emma Rice’s first production as artistic director at the Globe has provided controversy for the much-loved venue and tourist hotspot. Fans of Rice’s work with her previous company, Kneehigh, will recognise some techniques here. But applied to Shakespeare, her irreverence and inventiveness proves invigorating.

First a caution – for some odd folk – this approaches Dream: The Musical. No excuse necessary, but it is striking how much of the play is sung. Stu Barker’s score is accomplished, dramaturg Tanika Gupta’s lyrics (drawing on the Sonnets and John Donne) are exciting and the singing West End standard. There’s a clever Indian twist and an electric sitar, so let’s describe the sound as Bollywood Rock. Is Rice being provoking? I do hope so.

Raucous is de rigueur at the Globe but, for good or ill, Rice has upped the stakes. If it weren’t for fear of sounding hopelessly out of touch I’d suggest some age advisory warning. There were squeals of horror in the crowd at some pretty full-on audience participation.

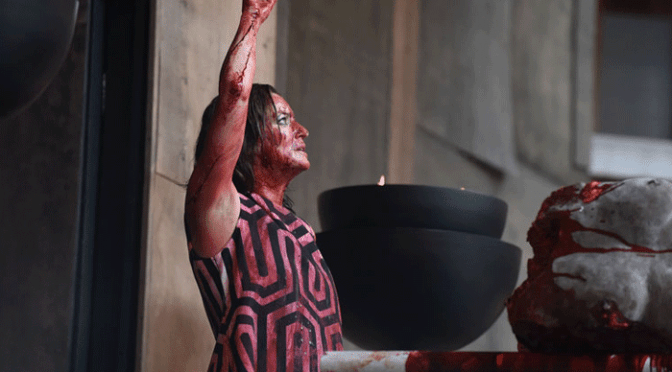

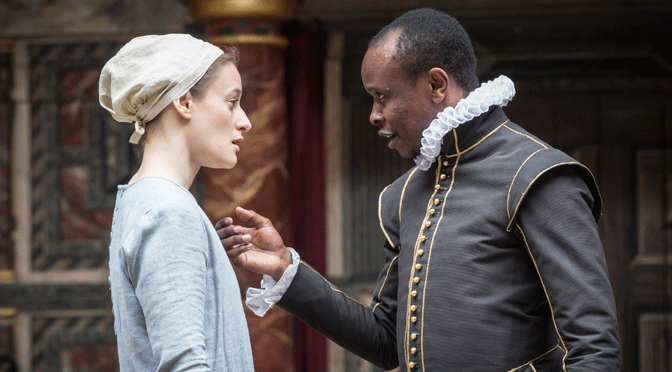

The show is sexy – many clothes are shed – and the polymorphous sexuality in Shakespeare is emboldened. Most impressively, with the King and Queen roles played by Zubin Varla and cabaret star Meow Meow – both intense performers –their chemistry is captivating. We’re reminded how creepy Titania being “enamoured of an ass” really is and both stars hold the stage, despite too much going on.

There are reservations. When Beyoncé is first quoted, your heart might sink at such an easy appeal to a younger audience. There’s a great deal of movement and some of it is messy. With water pistols, crazy costumes and a lot of accents, it’s anything for a lark. And the problem? Too many lines are difficult to hear, even lost. Rice lands the laughs, but they often fall at the expense of Shakespeare or, more generously, use the play as merely a springboard.

The hyped gender-bending casting (which is hardly new) may have been seen before, but not with the bite that Rice manages. Katy Owen does a superb job as Puck, working the crowd brilliantly, despite that water pistol. The rude mechanicals are recast as women. Only Bottom remains male – Ewan Wardrop doing the guys proud. Updating the wannabe theatricals into Globe volunteers is sweet and leads to excellent cameos, especially for Lucy Thackeray, whose calm ad lib, “my nephew’s gay”, tickled me pink.

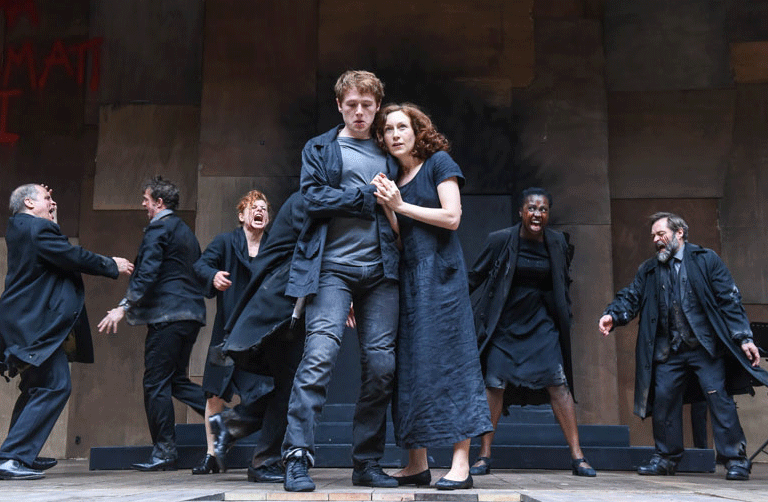

But it’s most with the Athenian lovers that Rice’s indiscretions are forgiven. Updating the couples into Hoxton hipsters is very funny. Ncuti Gatwa and Edmund Derrington make an energetic Demetrius and Lysander. Anjana Vasan gets roars of approval for her very modern Hermia. Ankur Bahl plays –hold on – Helenus, with wit and courage. There’s more to this decision than giving the line “ugly as a bear” a new twist. An uncomfortable response from some, admittedly young, audience members gives pause for thought. The Globe is a global institution (listen to how many visitors are from abroad). To see love between two men portrayed with complexity on such a stage is remarkable. There may be touches of over enthusiasm here but Rice balances public appeal with a radical streak that makes this show, and her direction, one of the most exciting things around.

Until 11 September 2016

Photos by Steve Tanner