Mike Bartlett’s biggest hit to date, Charles III, has made a much-deserved transfer to the West End after rave reviews at the Almeida. Billed as a ‘future history play’, Bartlett imagines Prince Charles ascending to the throne and a constitutional crisis that arises when he refuses to sign a bill privileging privacy over the freedom of the press.

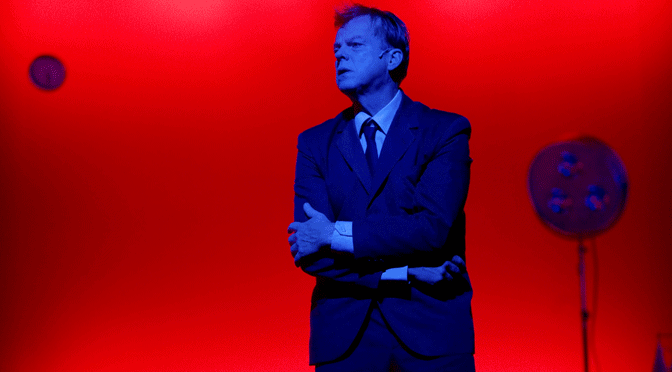

As well as being topical and very funny, the ideas are so outlandish – especially the presence of Princess Diana’s ghost – that it might all have turned out a bit silly. But it works. Royally. With a set of buzzing performances headed by a superb Tim Pigott-Smith in the title role, all the actors manage a fine balance between impersonation and a deeper intent. There are laughs at first, but these are well-developed roles and the serious subject matter is fascinating. Director Rupert Goold is uncharacteristically restrained; he knows the play speaks for itself.

Bartlett takes on the Shakespearean mantle with courage and panache. The play is written in verse, a demanding choice that adds humour and holds the attention. References to Shakespeare’s plays are light; it’s not so much the form and language that Bartlett borrows from the Bard as those ambitious themes of responsibility, family and identity – all of which are dealt with so intelligently that the royal soap opera is left far behind.

Not that the house of Windsor doesn’t make great raw material. The drama of youth vs experience, so ably depicted by Princes Harry and William (two sides of Shakespeare’s Hal?), is embraced by actors Richard Goulding and Oliver Chris. Imagining future events in such a fashion makes the heritage of Shakespeare’s history plays a kind of prism, creating layers of speculation. Bartlett handles the possibilities with wit, ensuring that Charles III is both entertaining and unpredictable, while raising big questions and creating real pathos.

Until 31 January 2015

Photo by Johan Persson

Written 23 September 2014 for The London Magazine