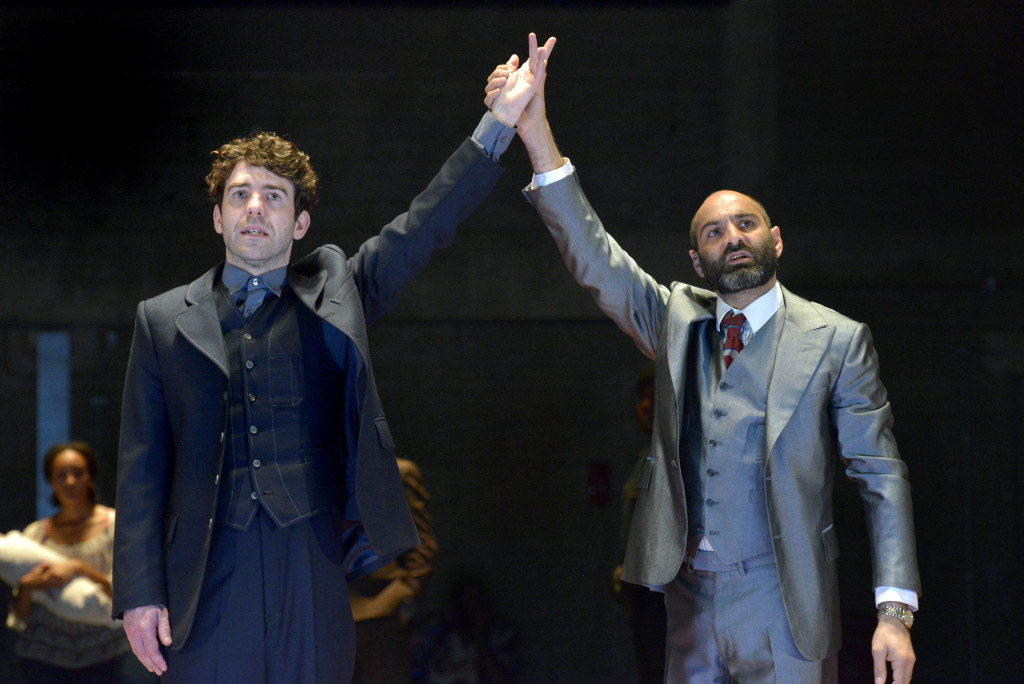

What a play. This late work from Tennessee Williams, which premiered at Hampstead back in 1967, is a mind-blowing exploration of fear and metatheatricality. And what a production. Director Sam Yates and accomplished performers Kate O’Flynn and Zubin Varla command this hugely complex script. Yates makes a strong argument for Williams’ vision and his precocious eccentricities, making them theatrically compelling and appropriately terrifying.

The scenario is far from simple. Two actor siblings, struggling in many ways, perform a play within a play. Felice and Clare are vivid creations, like the roles they adopt. But as The Two Character Play we watch carries on, it reflects, mimics and then – maybe – shapes their lives. Felice has written the piece, but it is changing as they they both perform it. Oh, and it has no end. Don’t worry, nobody is more confused than the characters themselves.

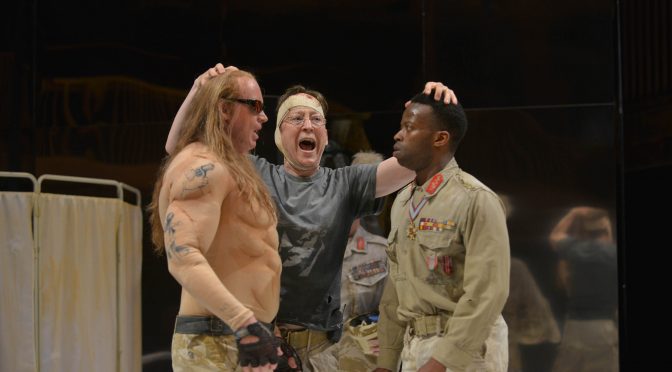

The brother and sister in the play are trapped at home – I did wonder if the play was chosen for staging during lockdown – while Felice and Clare are trapped in the theatre (quite literally). The claustrophobia is intense and grows as we learn about all four characters. Trauma and phobia multiply. The use of stage – which seems simply huge one moment and confining the next – is brilliant.

Williams’ language is a wonder. The poetic imagery, so full of the senses, means some lines stun. And the metatheatrical references, handled with bravado, include addressing the “stranger than strange” audience and speaking stage directions out loud. Clare’s live ‘edit’ of the script is signalled by a key played on the piano; O’Flynn even approaching the instrument becomes charged.

Yates brings just the right amount of lucidity to proceedings. With themes common to Williams’ plays, there’s a suggestion of self-parody that is often funny. O’Flynn has an exquisite delivery of some deadpan lines. Best of all, a sense of spontaneity is injected into a script that you could easily argue is contrived. Rather, the script itself seems alive!

Make no mistake – the mood is forbidding. Williams used dreams in his work throughout his life. But here we have a nightmare. Fear of performing is only the start as the characters’ lives, and their show, descend into darkness. Improvisations are fraught as the story unfolds to becomes more and more disturbing. Varla makes Felice a hugely sympathetic character – his performance is deeply moving. But the show is downright scary with a last half hour full of tension… and a gun.

All this drama is brought to the stage magnificently by Yates. With all manner of lighting and sound effects (Lee Curran and Dan Balfour) along with live video recording and projections (Akhila Krishnan). And Rosanna Vize’s set is perfect for the destabilising, fluid script. The Two Character Play is like being inside the minds of several mad people. Taking us into that condition makes unforgettable, amazing theatre.

Until 28 August 2021

Photos by Marc Brenner