Director Atri Banerjee’s excellent 2022 revival of the Tennessee Williams’ classic benefits from a strong focus on the text and a sensual creative vision. Both are aided by Rosanna Vize’s brilliantly sparse design: the set is a neon sign of one word – Paradise. The hopes and wishes of the characters are contrasted with the bare space before us.

There are a few small props. And the pole the sign is on rotates. But the stage is used to tremendous effect by movement director Anthony Missen. The cast hovers or runs around a circular platform – stepping on to it becomes a statement – and frequently walks backwards. Every moment is considered, every move worth watching.

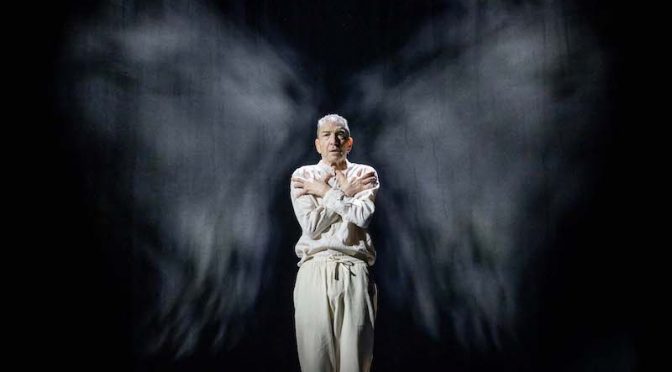

Light and sound become especially important, showing brilliant work by designers Lee Curran and Giles Thomas. The latter’s music for the show is fantastic, full of romance and melancholy, while the use of microphones (when characters argue, whisper or make telephone calls) is smart. And what you hear is surprising, too (let’s just from say from now on a particular Whitney Houston song will make me think of this show). Curran’s lighting includes golden glows and candlelight, suggesting love or nostalgia, or harsh shadows and a shocking flash for stark realisations.

All this before a collection of impressive performances – a further commendation for Banerjee – is addressed. The production is spacious – literally – but also in terms of the room given to develop characters. Consequently, the dreamlike quality Williams tells us about builds.

Kasper Hilton-Hille takes the role of Tom. He’s perfect casting as an angry “selfish dreamer” with just the right balance of quirk, cruelty and regret (by the end, he has tears in his eyes). Although Tom leads the show as narrator with easy command, Banerjee makes sure this is a particularly even production, with time for every character.

There are strong, intelligent performances from Geraldine Somerville and Natalie Kimmerling as mother and daughter, Amanda and hypersensitive Laura. At first, Amanda may seem a cold scold, but she shows a genuine affection for her children that is moving and steers us away from Williams’ exaggerations. Laura might seem not “peculiar” enough… at least until she wears a neon dress for gentleman caller Jim’s arrival. And it is with this scene that Kimmerling comes into her own.

The conversation between Laura and Jim has some of their dialogue repeated and includes a dance that Laura imagines. It illustrates how special Laura is. Her vivid imagination becomes a thing to cherish, her dance a parallel with her brother Tom’s poetic ambitions. The extended scene also means a larger role for Zacchaeus Kayode, who makes Jim vulnerable as well as charming, an admirable figure. While the production is superb throughout, I suspect this scene was key for Banerjee. It really is brilliant and makes for a particularly moving menagerie.

Until 4 May 2024 then on tour

Photos by Marc Brenner