Wearing his director’s hat, Patrick Marber has excelled with this revival of Tom Stoppard’s 1974 play. A characteristically dense affair, it uses the flawed reminiscences of an English diplomat in Zurich, one Henry Carr, to bring together Lenin, James Joyce and Tristan Tzara, thus covering politics, literature and art. You need to pace yourself to keep up.

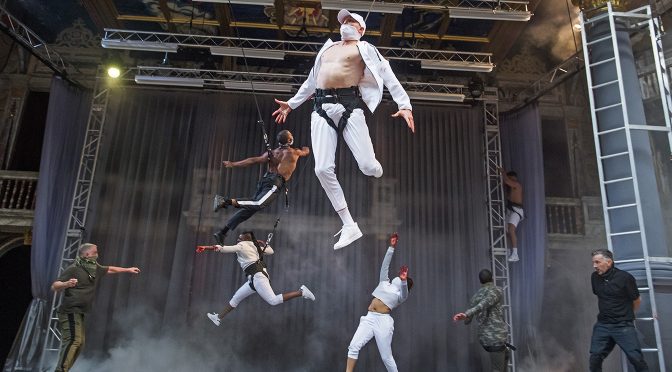

Formally inventive, Stoppard uses speeches, verse and songs, while modifying Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (if you need a reason, Carr performed the play in his youth). The elderly Henry suggests his memoirs could be a collection of sketches, and Marber embraces this to create some vaudeville scenes worthy of Cabaret Voltaire. Carr’s dementia is a wicked parallel to free association, ironically utilised in this satisfyingly controlled puzzle of postmodern plenitude.

Carr observes that as an artist you have to “pick your time and place” and in choosing such a fertile moment in European history, applying his own frame and distorting it, Stoppard has the audience enthralled. OK, it’s difficult to imagine many erudite enough to get their heads around the whole thing (you’d have to be as clever as, well, Tom Stoppard), but it’s great fun trying to keep up. It’s so crammed with humour that getting just half the jokes makes it worth it.

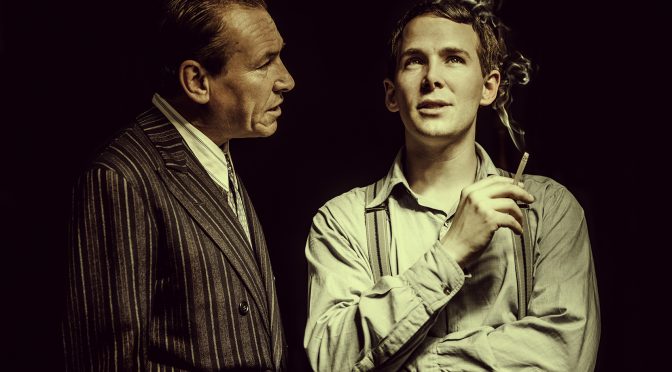

There’s a lot going on in Henry’s head, and Tom Hollander’s finest moments come when memories overwhelm his irascible character. Playing his younger self, he makes the comedy work hard. Stoppard even provides the review for his lead actor: parts don’t come much more demanding than this and Hollander really is superb. This this is a technically brilliant performance, the aged voice truly remarkable.

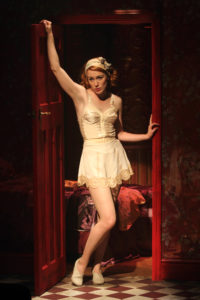

The rest of the cast seem spurred on by Hollander’s star turn, making each role memorable. Freddie Fox is superbly cast as the decadent Tzara – his switch to Wildean mode is faultless. Peter McDonald and Forbes Masson manage to make, respectively, Joyce and Lenin men you can laugh with as well as at. Clare Foster and Amy Morgan’s witty singing battle as Cecily and Gwendolen is a highlight in a show that has no shortage of brilliant moments. Stoppard and Marber run from any potential the play might have toward pretention. Just don’t forget to take a breath yourself.

Until 19 November 2016

www.menierchocolatefactory.com

Photos by Johan Persson