It’s hard to go wrong with the revivals that make up part of the exciting programming at Neil McPherson’s west London venue. The chance to see moments of theatrical history, always produced to the highest standard, is a great opportunity. This first London revival in 80 years of a smash hit from 1933 fits the bill perfectly.

Following our sensitive hero, Charles Tritton, through his time at medical school, the piece might be considered a coming of age drama. How this bright young thing deals with the world through the men he meets, students of different ages, is a neat exploration of socialization. Sophisticated older figure Paul, the lazy and libidinous Gilbert, or nice but dim Harvey are all potential models for Charles. These characters work in relation to Tritton, but are thought-provoking in their own right.

What Charles takes from these other men with regards his relationships to women isn’t much of a plot. The play’s focus becomes a love triangle between the girl Charles’ mother wants him to marry and another, Anne, he meets while studying. That his intended fiancée, Jill, is described as a “proxy sister” makes the drama falter for a contemporary crowd. Overall, it’s hard to appreciate the pressure here. Thankfully, Hodge doesn’t want it to be hard work; the dialogue is rich and director Geoffrey Beevers impeccable work provides time to explore its humour.

Although the roles are uneven, it is with characters that The Wind and the Rain is at its best. Charles is a strong central figure and the performance from Joe Pitts is enjoyable. Pitts has confused anxiety down pat (no small achievement) but also follows the character’s growth skilfully. The performance claims sympathy for Charles and his vaguely Bohemian views, even though efforts to consider others end up oddly selfish! Privileged and moody, spoilt even – Pitts does a great job showing it all.

While outnumbered on stage, the women in the show do well. There’s a neat comic part for the excellent Jenny Lee as the land lady. But it’s the love interests that excite. It would be easy to roll eyes at some of this writing: Jill is giggling and giddy, Anne far too self-sacrificing. But wait a moment. Two brilliant performances from Helen Reuben and Naomi Preston-Low respectively elevate these characters. Reuben brings out some of the show’s best humour and a steely edge that shows what a careful study her work is. Preston-Lowe secures the independence of her character while adding the romance the piece demands.

The Wind and the Rain ran in the West End for over a thousand performances; this revival is a glance at the theatrical mainstream, rather than the avant-garde, of the past. If the play strikes contemporary audiences as quaintly old-fashioned, maybe too slow with a thin plot, its dialogue and characters intrigue. As a guess, the excellent performances in this conscientious revival are the key to understanding the play’s success both then and now.

Until 5 August 2023

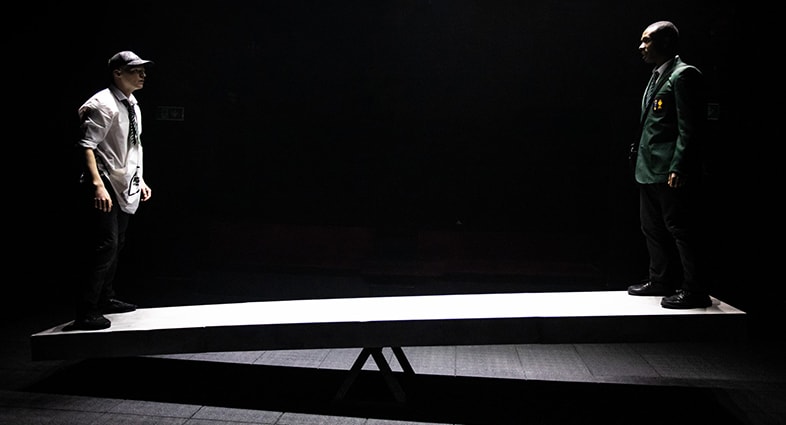

Photo by Mark Senior