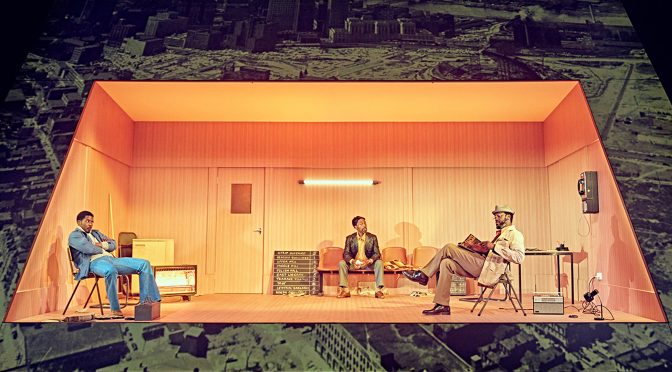

August Wilson’s great play gets a good revival under the directorial guidance of Tinuke Craig. Set in the office of a taxi company (the cars give the play its name) the piece is a close look at a community, full of emotion and drama.

The co-op business is headed by the admirable Becker (Wil Johnson) who is struggling to keep the premises open and about to meet his son who has just been released from prison. Old-time drivers struggle with drink (leading to a sensitive performance from Tony Marshall) or their past, while in conflict with a younger generation. Arguments between the gossiping Turnbo and the aptly named Youngblood are a highlight and make strong scenes for Sule Rimi and Solomon Israel. In all cases, Wilson’s characterisation is impeccable.

Unlike the writing, the performances are uneven. Some scenes feel more rehearsed than others. It’s an odd fault but Johnson – who is outstanding – possesses considerably more confidence than his colleagues which leads to uncomfortable moments. Johnson’s is a performance not to be missed as he portrays his character’s dignity and trauma with considered attention and intense passion. The production sags after Becker and Johnson finally leave the stage.

The play’s 1970s Pittsburgh setting is evoked in costume design and video projections (strong work from Alex Lowde and Ravi Deepres). But the period feel doesn’t always come through in performances – accents are hit and miss and the odd declamatory moment jars.

The production works from firm ground though. There’s an excellent balance between humour and darker moments that shows the writing’s sense of rhythm. And some serious thought-provoking antagonism as younger characters – Becker’s son especially – are told to take responsibility for their lives. Wilson draws us into the characters’ complex lives with consummate skill and Craig’s calm understanding of script’s strengths ensure the revival’s overall success.

Until 9 July 2022

Photo by Manuel Harlan