One area of director Ivo van Hove’s considerable expertise is monologues. As with a former fantastic production, Song From Far Away, close work with a single performer and an intense script can yield powerful results. This show, starring Hans Kesting, shares potent subjects and fantastic acting that deserves acclaim.

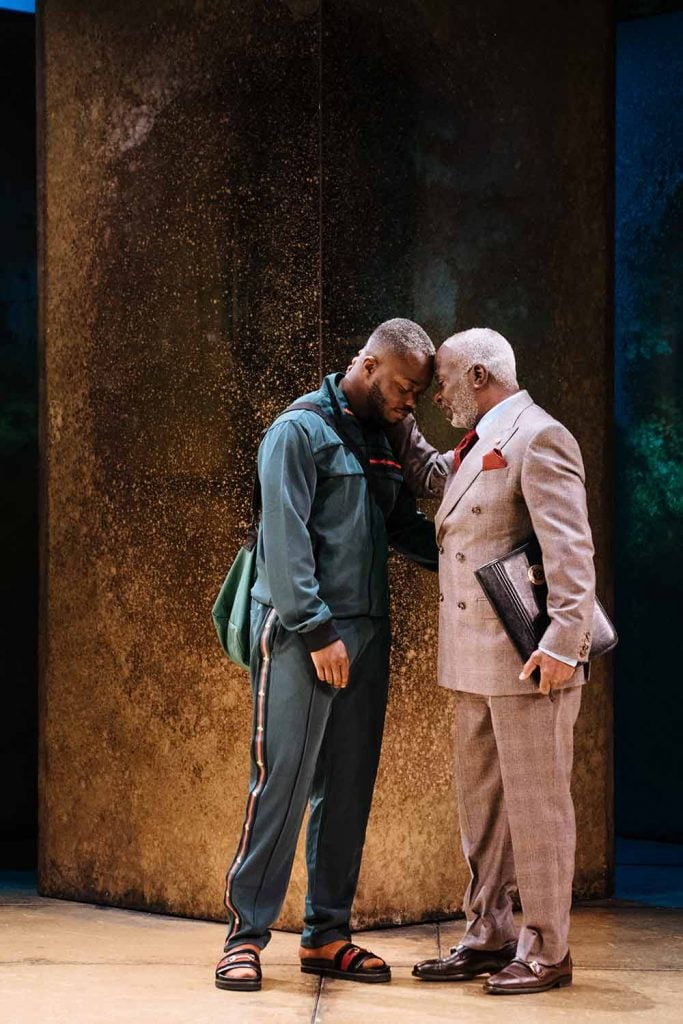

Adapted by van Hove from the book by Édouard Louis, Kesting takes the author’s voice as well as depicting his parents. Growing up gay in rural France, dealing with his father’s homophobia and violence, are exposed in harrowing detail. These sections have undoubted force.

Yet the title tells us this is a work about a father as much as a son. It’s a memoir and a political lecture. How the father is a victim of violence himself – by the ruling classes – is Louis’ concern. Along with the repercussions on both men in the past and present. How the personal and the political imbricate is the point laboured. But I’m not sure it works here. And it’s not because Louis is incorrect. The source material (and Returning to Rheims by Didier Eribon which covers similar ground, if you’re looking for further recommendations) is worth reading. The problem lies with the adaptation.

The “negative existence” of the father’s life arrives too late. It’s understandable that the author discovered this as an adult. But for the audience, there’s a lot of Louis – and the trauma around a childhood performance of a pop song – to get through first. Dramatically, the impact of life limitations on his father feels rushed. The theatricality of the show is aided by Jan Versweyveld’s sound and lighting design. But van Hove’s adaptation sells his source material short and given the director’s track record, that disappoints.

Until 24 September 2022

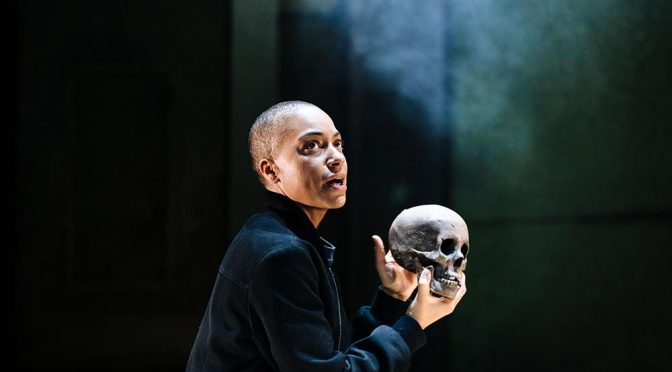

Photo by Jan Versweyveld